Edwards still on winning streak against Meril at UPC Court of Appeal

Edwards Lifesciences has secured another victory against Meril Life Sciences at the UPC. The Court of Appeal has upheld both the revocation judgment from the central division Paris and the infringement ruling from the local division Munich. As a result, Meril remains unable to sell its Myval Octacor heart valves in UPC territory. The Court of Appeal has used this decision to provide further guidance on UPC revocation actions.

28 November 2025 by Mathieu Klos

The dispute over heart-valve patents predates the UPC’s launch. When the European court opened on 1 June 2023, Edwards promptly filed an infringement lawsuit against its Indian competitor at the Munich local division concerning EP 3 646 825. Meril countered with both a central nullity action at the Paris central dvision and a counterclaim for revocation at the Munich local division, which was later referred to Paris.

The Paris central division then heard both challenges to EP 825’s validity together and, in its first ruling since the court’s launch, upheld EP 825 in amended form in mid-2024. Both parties appealed. Meanwhile, the Munich local division continued with the infringement case. In autumn 2024, the Munich panel under presiding judge Matthias Zigann found that Meril’s Octacore THV device infringed EP 825. Meril appealed this decision.

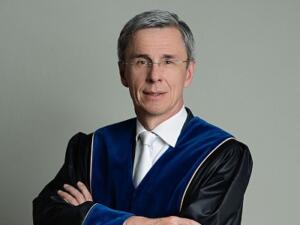

Now, two and a half years on, the EP 825 dispute has reached its conclusion. The UPC Court of Appeal’s 1st panel, under presiding judge Klaus Grabinski, has upheld both the Paris revocation decision and the Munich injunction.

- Klaus Grabinski

- Peter Blok

- Emmanuel Gougé

Despite Meril’s hopes for a more favourable validity ruling on EP 825, the company remains barred from selling its Myval Octacor heart valves in 16 UPC member states (case ID: UPC_CoA_464/2024 and others).

The 1st panel of the Court of Appeal, comprising Klaus Grabinski, judge-rapporteur Peter Blok and Emmanuel Gougé, along with technically qualified judges Elisabetta Papa and Max Tilmann, largely upheld the first instance decisions.

- Elisabetta Papa

- Max Tilmann

Economic impact

Edwards’ UPC actions against Meril extend beyond EP 825, encompassing five other patents across various UPC divisions. The proceedings focus on Meril’s transcatheter heart valves (THV) Myval, Octacor and Octapro, as well as the Navigator delivery system.

Edwards asserted patent infringement at the Munich local division based on three patents, with two more at the Nordic-Baltic regional division in Stockholm and one in Paris. Meril responded with counterclaims for revocation and revocation actions at the Paris local division. A full overview of the proceedings is available here.

With the Court of Appeal’s latest judgment, five of the six actions have now been decided in the final instance or settled. Consequently, Meril is currently unable to sell three older generations of its heart valves — Myval, Octacor and OctaPro – in various European countries.

The Meril website states: “The Myval (alone or with Navigator) and Val-de-Crimp systems are not available for sale in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, and Sweden.”

It further notes that “the Myval Octacor system and Myval OctaPro system (with Navigator Pro or Navigator Inception) are not available in the above countries except Romania”.

Meril has one final opportunity to turn the tide at the Court of Appeal. The Paris central division recently upheld Edwards’ EP 4 151 181 in amended form, finding infringement and issuing another sales ban against Meril’s Octacore and Octapro series. Meril has the option to appeal this ruling but has not yet decided.

Legal impact

While Meril’s situation in Europe remains unchanged, the Court of Appeal ruling has significant legal implications for future revocation actions. As with its Amgen vs Sanofi ruling, the Court has taken the opportunity to provide guidance to parties and first-instance divisions on key issues in revocation actions.

Experts view the simultaneous publication of the Amgen vs Sanofi and Edwards vs Meril judgments as a coordinated effort by the court to address important principles. The 2nd panel under presiding judge Rian Kalden decided Amgen vs Sanofi, while the 1st panel under Klaus Grabinski ruled on Edwards vs Meril. The two judgements feature a total of 39 headnotes, with both panels focusing extensively on assessing inventive step in revocation actions. Key headnotes on inventive step are nearly identical in both judgments: headnotes 10 to 16 in Amgen vs Sanofi and headnotes 7 to 12 in Edwards vs Meril.

Leaning towards German case law

For instance, the Edwards vs Meril decision states in headnote 12: “A starting point is realistic if the teaching thereof would have been of interest to a person skilled in the art who, at the effective date, wishes to solve the objective problem. This may for instance be the case if the relevant piece of prior art already discloses several features similar to those relevant to the invention as claimed and/or addresses the same or a similar underlying problem as that of the claimed invention. There can be more than one realistic starting point, and the claimed invention must be inventive starting from each of them.”

The court continues in headnote 12: “The person skilled in the art has no inventive skills and no imagination and requires a pointer or motivation (in German: “Anlass”) that, starting from a realistic starting point, directs them to implement a next step in the direction of the claimed invention. As a general rule, a claimed solution must be considered not inventive/obvious when the person skilled in the art would take the next step, prompted by the pointer or as a matter of routine, and arrive at the claimed invention.”

Experts note a clear tendency towards German case law, which assesses the inventive step using a “motivation”-related approach, often described as “holistic”. According to experts, the court does not follow the European Patent Office’s “problem solution” approach.

Unlike the Amgen vs Sanofi judgment, the 1st panel judges address fundamental issues of competence, admissibility of patent amendment applications, permanent injunctions and interim cost awards in their judgment.

Three firms for Edwards

With the UPC dispute spanning divisions in several countries, both parties rely on international teams from different law firms, assembling their teams depending on the local division.

In Paris and at the Court of Appeal, Edwards relied on a UK team from Powell Gilbert led by lawyers Siddharth Kusumakar and Bryce Matthewson. Bernhard Thum and Jonas Weickert from German patent attorney firm Thum IP argued the validity part in Paris.

- Siddharth Kusumakar

- Boris Kreye

- Bernhard Thum

Munich-based Bird & Bird partner Boris Kreye, together with Thum, was Edwards’ main representative in the infringement case at the Munich local division and again part of the team handling the appeal.

All three firms represented Edwards also in the court of Appeal proceeding. The overall team also includes Powell Gilbert associates Dan Down and Adam Rimmer, as well as Bird & Bird lawyers Elsa Tzschoppe and Ioana Hategan.

Four firms for Meril

Unlike the first-instance proceedings, where Gide led before the Central Division Paris and Hogan Lovells led the infringement proceeding in Munich, Hogan Lovells took the lead in the Court of Appeal proceedings on behalf of Meril.

However, all firms instructed by Meril in the first instance also worked on the appeal. A large team from Hogan Lovells was again led by Düsseldorf-based partners Andreas von Falck and Alexander Klicznik, who are also coordinating the overall dispute Europe-wide for Meril.

- Andreas von Falck

- Jonathan Stafford

- Alexander Klicznik

Furthermore, UK patent attorneys Jonathan Stafford and Gregory Carty-Hornsby from Marks & Clerk provided technical advice in all UPC proceedings. They have previously advised Meril in EPO proceedings as well.

Emmanuel Larere and Jean-Hyacinthe de Mitry from Paris-based firm Gide Loyrette Nouel represented Meril in the Paris case and were again involved in the appeal. They worked with a team from Regimbeau. The firms formed a cooperation in patent litigation at the UPC in 2023.