UK to cost-cap civil actions as number of patent cases declines

In 2022, the number of new patent cases filed at the UK High Court once again dropped significantly. At the same time, however, the court handed down some landmark decisions in high-profile disputes. To reduce costs, the judiciary is now planning a cost cap for the Short Trial Scheme, which also covers mid-tier patent disputes.

3 April 2023 by Konstanze Richter

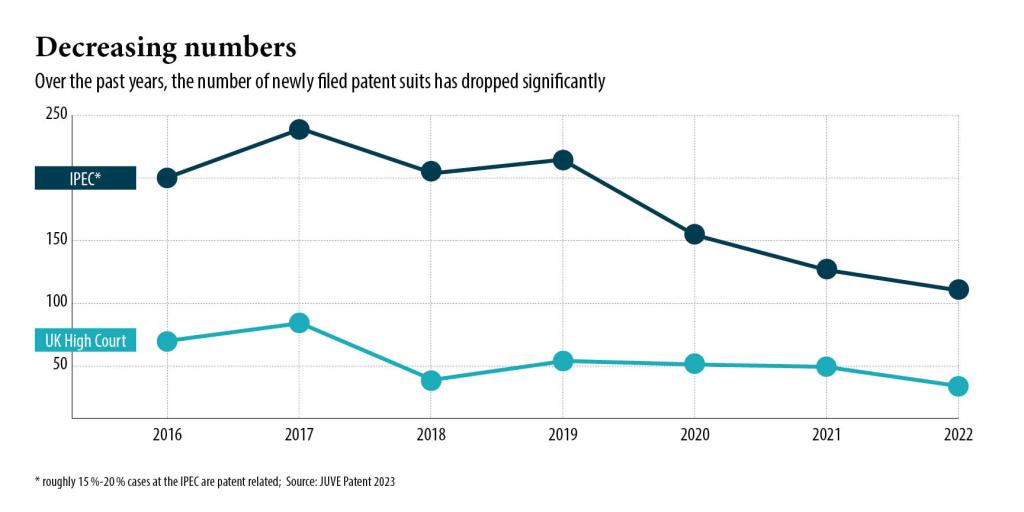

According to civil justice statistics, the number of new patent cases being filed at the first-instance UK High Court is continuing to decline. 2022 saw just 35 new patent actions, a 30% decrease compared to the previous year. In 2021, companies filed 50 new lawsuits; even in the COVID-19 year of 2020, the court counted 52 newly filed cases.

However, over the twelve months of 2022, the new suits spread out evenly over all quarters of the year. Previously, patent cases had often accumulated after the third quarter.

Patent cases decrease

For several years, there has been a trend towards parties filing fewer patent suits at the first-instance High Court, which under the Chancery Division has the remit to hear patent cases. Although there are always fluctuations, for example, 71 new actions in 2016 were followed by 85 in 2017, a clear long-term trend towards fewer court cases is emerging. Judging by the court case numbers from 2022, the slump is now particularly significant.

High workload remains

Figures at the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC), a specialist subdivision within the Business and Property Courts of the High Court, also reflect a downwards trend. IPEC presiding judge Richard Hacon hears patent disputes of small and medium-sized companies, many of which are considered of minor economic importance. However, one main difference to the High Court is that the IPEC permits patent attorneys to litigate.

Last year also saw the total number of new IPEC lawsuits reach a record low of 112. Experts estimate that typically 15% to 20% of IPEC cases concern patents, while the rest involve soft IP such as trademarks, design or copyright.

At the same time, lawyers interviewed by JUVE Patent claim that patent judges are not seeing any less work. The court calendar corroborates this fact, listing trials in high-level patent disputes including Apple vs. Optis, Neurim against Teva and Alcon vs. AMO. According to patent experts, the settlement rate is also very low.

Complex FRAND patent cases

The judges’ high workload is partly down to parties filing many more complex cases than before, especially in the field of telecommunication, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices. Additionally, proceedings in London tend to involve several patents from one family as well as numerous defendants, for which the court schedules several hearings.

The statistics show that, in almost three quarters of patent cases, at least one disputing party is from overseas or the EU. This indicates that the UK remains an attractive court location for patent litigation.

The statistics show that, in almost three quarters of patent cases, at least one disputing party is from overseas or the EU. This indicates that the UK remains an attractive court location for patent litigation.

SEP holders are especially keen to bring their complex FRAND trials before the British courts. With the recent ruling in InterDigital vs. Lenovo, the High Court once again established itself as the go-to location for FRAND rate setting.

Wait-and-see mode

Exactly what is driving the drop in new suits is unclear. Since patent litigation in British courts is often very costly, one reason for companies holding back could be economic considerations.

Other patent holders may be waiting to see what the UPC will bring. When it comes to pan-European patent disputes, where the UK is only one market of many, the new court could prove a competitor to the British patent courts.

As such, the judiciary is behind efforts to make the British patent courts even more appealing – especially with regard to costs.

Capping costs for cases

IPEC proceedings are already subject to a financial limit of around £500,000 in damages and £60,000 in costs. For complex patent disputes at the High Court, which could have a value reaching many millions of pounds, the costs alone can quickly add up to between £1 million and £5 million or more. This sum includes court fees, legal fees for solicitors and barristers, and, if needed, for technical experts.

Overall, the various considerations make the UK an expensive venue for patent disputes. Michael Burdon, patent litigation partner at the London office of Simmons & Simmons, says, “It is very difficult to predict costs accurately with confidence at the beginning of High Court proceedings. This is due to the potential range and complexity of issues which might be raised, which also evolve and expand during the proceedings and which can also increase the length of the trial, which is a major part of the cost.”

But the UK judiciary is going some way towards mitigating the costs for litigating parties. Last year, the Civil Justice Council created a Cost Working Group which aims to make civil actions more cost effective and thereby more accessible also to SMEs. The working group conducted a public consultation in 2022, inviting shareholders to make proposals for capping costs.

Time limit

Michael Burdon

Since 2018, the High Court has also offered a more streamlined procedure through its Shorter Trial Scheme (STS). The scheme limits the length of STS trials to four days, with the court allocating claims to the judge at the time of the first case management conference or earlier.

The STS, which covers all manner of issues brought before any of the Business and Property Courts of the High Court, is permitted to cover cases which do not involve allegations of fraud or dishonesty. It can also pertain to cases which do not involve multiple issues or multiple parties.

The courts have already successfully applied the STS in patent cases, including Facebook against Voxer and Insulet against Roche Diabetes Care.

However, while the STS makes trials shorter where possible, so far its costs are no more predictable than in regular patent cases. For the court system to introduce a formal cost cap, a change to the rules of procedure would be necessary.

The Intellectual Property Lawyers’ Association (IPLA) has now submitted a proposal for capping costs for patent cases in the STS in response to the public consultation by the Costs Working Group. The association represents about 65 IP law firms in the UK. It is designed for mid-tier cases, which are less complex and valuable than the types of cases the patent court conducts, but which are more complex and valuable than an IPEC case.

For mid-tier patent cases

In the proposal, Burdon, who is also IPLA chairman, states, “The main reason for the proposal is to improve access to justice for mid-tier patent disputes by providing potential litigants with greater certainty about the total costs risk of commencing proceedings”.

The IPLA proposal adopts the current procedures for the STS, adding a single total costs cap of £500,000. “IP disputes make up a substantial proportion of the cases heard in the STS already. We calculated and justified the cost cap, in part, according to the experience from these proceedings”, he says. “This amount should enable the successful party to recover a reasonable proportion of their total costs.”

After all, the IPLA proposal states, “it is the overall cost of litigation which is considered by industry and experienced users to be the most important criterion in deciding whether to fund the issue or defence of proceedings.”

By capping costs for patent cases and streamlining proceedings, the UK is looking to attract more SMEs. It also wants to become more appealing in general for patent disputes that parties can bring in different international jurisdictions. Burdon says, “We need to make sure the UK court system is efficient and fit for purpose for all types of patent disputes”. According to him, there is a strong likelihood that the courts will introduce a cost-capping system over the course of 2023.