“Insiders’ tip”: Scandinavian patent market grows in eminence

The Scandinavian market is considered an insiders' tip in the UPC system, especially for patent firms from the UK. Divisions in Stockholm and Helsinki received their first cases early on after the UPC launch. Since then, the number of cases has developed slowly – but the national patent markets in Denmark, Finland and Sweden continue to make their mark.

24 April 2024 by Mathieu Klos

Even before the UPC launched, UK law firms took an early liking to the Scandinavian patent market. For example, Potter Clarkson, a mixed IP law firm dominated by patent attorneys, opened its first offices in Stockholm and Lund in 2016.

Today, the firm best known for serving the life sciences industry has five offices in Sweden and Denmark, but only two in the UK. The firm’s management also recently hired a Norwegian lawyer, although it has not yet established a presence in the country.

EIP is another mixed UK IP firm that has ventured into Scandinavia. In 2022, EIP opened an office in Stockholm with five patent attorneys brought in from various Swedish IP firms. Unlike Potter Clarkson, however, EIP has not yet established a lawyer practice in Scandinavia, although it too answered the call from existing Scandinavian clients to expand its local business. In 2023, the then-imminent launch of the UPC also played a role in the firm’s considerations.

Ideal framework

Since 1 June 2023, UK law firms have developed a vital interest in the three Scandinavian markets participating in the UPC. Denmark, Finland and Sweden all host a UPC division: Denmark and Finland each have a local divsion, while together with the Baltic countries, Sweden hosts the Nordic Baltic regional division.

In discussions with JUVE Patent, several London-based patent litigation firms described the three markets as an “insiders’ tip”. They confirmed that they are keeping a close eye on how the region’s patent firms and UPC divisions are developing. Indeed, a leading patent litigator from London says, “The high level of specialisation of the judges and lawyers, the distinct service mentality in these countries, the good language skills – all of this makes the Scandinavian markets interesting for us.”

Thus, reliability, good language skills and a high level of service are criteria which clients consider when deciding whether to start litigation in a new international court. Traditionally, the UK and Scandinavia also have strong economic relations. Scandinavian patent litigators also confirm close relationships with London patent firms.

In particular, the two regions cooperate closely in large cross-border life sciences cases. Often, UK firms coordinate the battles and call in Scandinavian lawyers as local counsel.

Fruitful start for Scandinavia

The Nordic Baltic regional division made a fruitful start. Parties filed two lawsuits there on the UPC’s first day: Ocado filed a now-settled lawsuit against Autostore, while Edwards Lifesciences attacked arch-rival, Meril Life Sciences. Both parties also filed claims with other UPC divisions.

Currently, the Nordic Baltic regional division has five cases. ©Unified Patent Court

In July, the Helsinki local division also received its first case after AIM Sport filed an infringement and PI case against Supponor. Like the two actions brought by Ocado and Edwards Lifesciences in Stockholm, this dispute extended previous national litigation.

On the other hand, the Copenhagen local division was obliged to wait until 2024 for its first case. At the request of JUVE Patent, the court did not provide any details on this case. But, since the promising start, cases at the other two Scandinavian UPC divisions in Stockholm and Helsinki have only slowly trickled in.

Sluggish since August

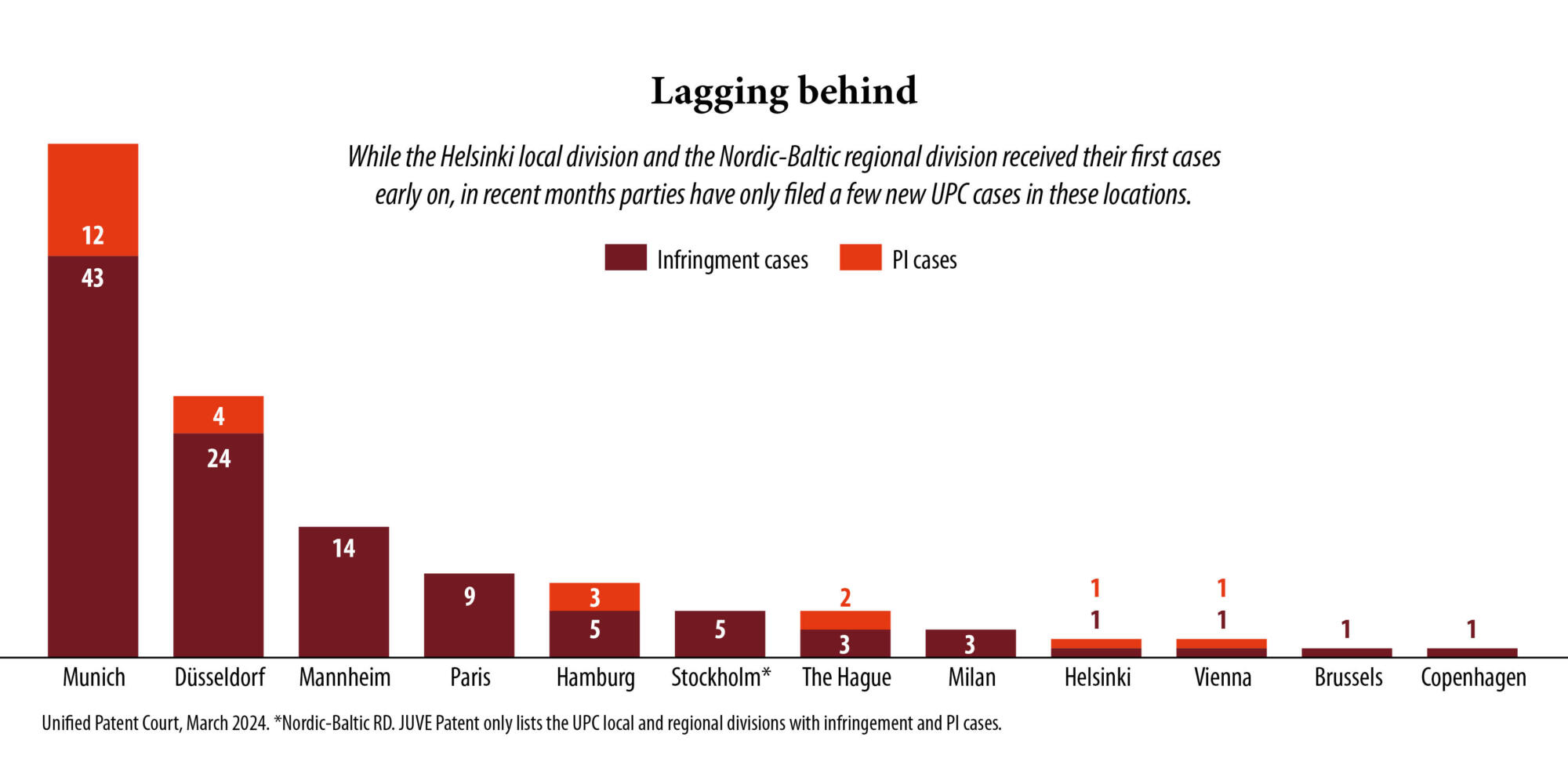

According to the UPC’s statistics on the current number of cases, which the court published at the end of March, the Nordic Baltic division currently has five infringement cases. Statistics also show eleven counterclaims for revocation. The two AIM Sport cases are pending in Helsinki.

In comparison, the Munich local division has 43 infringement and 12 PI proceedings, while the Düsseldorf local division has the second highest number with 24 infringement and four PI proceedings. In addition, the former has 64 counterclaims for revocation, with ten pending at the latter.

Such proportions are nothing new for Scandinavia’s judges and lawyers. According to Swedish lawyers, on average around 20 new cases per year have reached Sweden’s first-instance court, the Patent and Market Court in Stockholm, in recent years. The Sweden Patent and Market Court informed JUVE Patent that it saw just 12 cases altogether in 2023.

The situation in Finland is similar. The Market Court in Helsinki (markkinaoikeus), which is the first instance for patent proceedings, received 20 new cases in 2023. However, the court numbers for both courts do not include appeals against decisions of the respective patent offices. The Patent and Market Court in Stockholm and the Finnish Market Court are also responsible for these cases.

In summer 2023, one of the first UPC hearings took place in Helsinki in the battle between AIM Sport and Supponor. ©Unified Patent Court

JUVE Patent does not have figures for national patent proceedings in Denmark, which the Maritime and Commercial High Court in Copenhagen conducts. However, experts estimate that the numbers do not exceed the figures for patent cases at the Stockholm and Helsinki courts.

Scandinavian life science prowess

In Sweden, Finland and Denmark, the majority of patent proceedings are life sciences disputes. The courts in all three UPC countries and Norway have heard many disputes concerning important pharmaceutical and biotechnological drugs.

Oscar Björkman Possne

One example is the high-profile dispute between Bayer and Sandoz at the Stockholm Patent and Market Court. With the help of a Stockholm team from Mannheimer Swartling led by Oscar Björkman Possne, Bayer succeeded in upholding an important patent protecting its Xeralto product which treats thromboembolic disorders.

The drug is one of the German pharmaceutical giant’s top-selling products. Sandoz defended itself with a team led by Martin Levinsohn of Setterwalls.

In Scandinavia, the strong emphasis on healthcare-related litigation is not surprising. Not only do all three countries have highly developed healthcare systems, but two of the 20 largest pharmaceutical companies in the world hail from Sweden and Denmark in AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk, respectively.

Med-tech a hidden strength

However, just 21 million people live in all three countries combined. Japan, with its 125 million people, only has Takeda in the pharmaceutical industry’s top 20 list. Lundbeck is another well-known Danish pharmaceutical company. Scores of innovative Scandinavian biotech and medical device companies are active in this strong economic sector.

The three medical-technology infringement claims at the Nordic Baltic division further emphasises its judicial competence for such cases. In addition to the two lawsuits filed by Edwards Lifesciences against Meril, Abbott also filed a lawsuit against Dexcom in November concerning a glucose-monitoring device.

Furthermore, in Denmark, lawyers report that there are many disputes about parallel imports of medicines. Unsurprisingly, mobile phone cases also play an important role in Finland alongside life sciences. Nokia remains the country’s best-known company. However, lawyers from all three countries also emphasise that patent disputes in their countries are characterised by technical diversity across all sectors.

Henri Kaikkonen

Small market, few players

For the patent courts in Denmark, Finland and Sweden, it is not only the small number of cases brought by parties which are easy for the judges to deal with. According to JUVE Patent research, the number of prominent law firms with a good international reputation is high in relation to its overall numbers.

Among Swedish law firms with patent litigation practices, the best-known names are Gulliksson, Mannheimer Swartling, Setterwalls, Sandart & Partners, Vinge and Westerberg & Partners.

While the patent teams of Mannheimer Swartling, Sandart & Partners and Vinge represent pharmaceutical originators, Gulliksson is more than likely on the generics side. Market observers also frequently mention Setterwalls when it comes to firms which represent generic drug manufacturers in Sweden.

Oscar Björkman Possne, partner at Mannheimer Swartling, says, “The Swedish Bar Association is very strict when it comes to conflicts of interests concerning litigation. In a way, this makes it easier for law firms to choose one side or the other in the life sciences industry.”

However, lawyers from all firms emphasise that technical diversity characterises the patent disputes on which they work. Patent teams at Danish and Finnish law firms report the same finding.

Finland weighs in

In Finland, the most well-known practices are Borenius, Castrén & Snellman, Hannes Snellman and Roschier. The country’s lawyers also report similarly strict rules regarding conflict, with the market seeing a similar segmentation in life science disputes. Market participants mention Roschier as frequently representing originators, whereas Borenius is often on the opposing side for manufacturers of generic drugs or biosimilars.

Of the approximately ten law firms that practice patent litigation in Denmark, the best-known internationally are Bech-Bruun, Gorrissen Federspiel, Kromann Reumert and Plesner.

In Scandinavia, only a team in Helsinki represents Bird & Bird, which is one of Europe’s strongest patent litigation outfits. This is not surprising, as Nokia is one of the firm’s main clients. However, the Roschier patent team conducts proceedings for the mobile communications giant in Finland.

On the other hand, Hogan Lovells does not have a patent team in one of the Scandinavian countries. This is despite the heavyweight firm boasting teams in various others European hotspots for patent litigation.

Full-service firms dominate

Observers often remark that patent law is primarily a business for IP boutiques. If one looks at the legal landscapes in this segment in Germany, France or the UK, it rings true: IP boutiques dominate, even if multiple patent practices in full-service firms are just as active.

In Scandinavia, however, boutique firms only dominate the patent prosecution business, with only two boutiques among the top practices for patent cases. Both Sandart & Partner and Westenberg & Partners come from Sweden, with both specialising in IP and dispute resolution.

All other top teams are integrated into full-service firms. Borenius and Roschier are considered market leaders in Finland, but operate as part of national full-service firms. The latter is active in both Finland and Sweden.

Bech-Bruun, Gorrissen Federspiel, Kromann Reumert and Plesner from Denmark are national full-service firms, as are Gullikson, Mannheimer Swartling, Setterwals and Vinge in Sweden. These firms advise clients on everything from employment law to M&A, as well as IP.

Magnus Dahlman

Wider IP spectrum

Regardless of whether in a full-service firm or an IP boutique, all Scandinavian patent litigation teams have a high partner-associate leverage.

At Gullikson, for example, three equity partners are active in patent litigation while eleven IP associates provide support. At Setterwalls, ten associates work with the two partners, and Sandart has five partners who regularly conduct patent cases. Here, eleven associates and counsel provide support. At Borenius in Helsinki, there are 16 IP associates and counsel, but only two IP partners.

The high leverage ratio is not only because most teams operate in full-service firms, which usually have a higher leverage than boutiques as a business model. It also occurs due to patent cases in Scandinavia being more extensive than, for example, Germany. Scandinavian courts decide validity and infringement together. In the early stages of a patent case, there is often an intense discussion on validity.

In addition, Scandinavian teams tend to work more broadly in IP. Here, no partner works profitably from patent cases alone. Transaction advice, for example, can be an important source of income. In Helsinki, the Bird & Bird team around Henri Kaikkonen focuses strongly on advising tech clients. It also focuses on trade secret disputes alongside conducting patent litigation.

First UPC cases, first advisors

With the UPC, the Denmark, Finland and Sweden patent practice now have another high-calibre source of income. Currently, eight infringement and PI cases are pending across the three Scandinavian UPC divisions.

Anna Bladh Redzic

Sandart appears to have the most UPC cases under its belt. The law firm is advising Meril Life Sciences alongside Hogan Lovells in the dispute with Edwards Lifesciences in Stockholm.

For years, the two companies have fought over heart valves throughout Europe. Together with Powell Gilbert, Gulliksson is representing Edwards as plaintiff at the Nordic Baltic regional division.

Transparency dispute brings opportunities

A Sandart team around Anna Bladh Redzic is also advising another UPC client, Ocado, in a dispute with Autostore at the Nordic Baltic regional division. Here, the firm works with Powell Gilbert and other European law firms. Although the parties have settled the case, the UPC Court of Appeal recently dealt with the matter of permissibility of public access to court documents.

Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer partner Christopher Stothers, who is based in London, engaged the support of several other law firms. Among the eight parties involved for Stothers included Danish firm Kromann Reumert, which had applied for access to the documents. Sandart is reportedly also involved in another UPC case concerning medical products.

Gulliksson’s patent team, led by partner Magnus Dahlman, is also involved for Swedish company Aarke AB, which designs kitchen essentials. Soda Stream sued the party over water carbonation technology at the Düsseldorf local division. To date, Gulliksson has worked without the support of German lawyers.

The Helsinki local division is currently negotiating an infringement and PI case between AIM Sports and Supponor regarding modern advertising technology in sports stadiums. Roschier and Powell Gilbert represent AIM Sport, with two German law firms are also involved. Finnish law firm Hannes Snellman represents Supponor, with support from Hogan Lovells and Gleiss Lutz.

At the end of September, in what was one of the first full judgments at the UPC, the Helsinki local division rejected AIM Sports request for a preliminary injunction against its competitor. An appeal is currently pending against the judgment.

Shaping CJEU case law

Gulliksson also recently demonstrated its presence in pan-European cases for German electronics group BSH in a dispute with Electrolux over vacuum cleaners.

Ludvig Holm

In May 2022, the Swedish Court of Appeal referred a question to the CJEU concerning the jurisdiction of Swedish courts for ruling on infringement proceedings arising from non-Swedish parts of patents (case ID: E-339/22). Gulliksson represented BSH in the Swedish proceedings, while Westerberg & Partners is lead counsel for Electrolux. German law firms are also involved in the proceedings.

The Grand Chamber of the CJEU will now hear the case on 14 May. The decision could set the tone for cross-border injunctions.

In early 2024, the CJEU confirmed that Finnish law, which demands a strict liability principle in cases where a court overturns a PI, complies with the EU directive. Doubts as to its compliance arose from the interpretation of the strict liability standard in another CJEU case of 2019, C-688/17, which concerned Bayer Pharma vs. Gedeon Richter.

In view of this, the Finnish Market Court submitteda question to the CJEU in a damages dispute between Gilead and Mylan (now Viatris) over the SPC protecting HIV drug Truvada. Roschier acted for Gilead, while Borenius advised Viatris.

Strong ties to UK and Germany

Ben Rapinoja

It is striking that Powell Gilbert is involved in so many UPC cases in Scandinavia. The firm seems to have a particularly strong relationship with the region. But many Scandinavian law firms emphasise their good relationship to law firms from London. These often result from cooperation in large cross-border cases.

Ludvig Holm, partner at Westerberg says, “In bigger patent litigation, many Swedish firms are more at the receiving end and the teams are often coordinated from London.”

Anna Bladh Redzic, who recently worked for Ocado in the UPC transparency case, says, “Sandart & Partner traditionally has strong links to Germany and London IP firms, as can be seen from our recent work alongside Powell Gilbert for Ocado against Autostore at the UPC.”

Hogan Lovells is also involved in two UPC proceedings in the Scandinavian UPC divisions for Supponor and Meril Life Sciences. Both proceedings developed from national proceedings, with the German Hogan Lovells team in the lead. But the international firm engaged Hannes Snellman and Sandart respectively for the Scandinavian UPC proceedings.

However, one case in Stockholm is taking place without the involvement of Scandinavian law firms. Texport has filed a lawsuit against Sioen, with the support of Vienna-based Taylor Wessing partner Thomas Adocker, in a case concerning protective clothing. Latvia is the place of infringement, meaning Texport filed its suit at the Nordic Baltic regional division.

Emil Brengesjö

A common law tradition

Although parties filed all UPC claims in Helsinki and Stockholm in English, the coordinating law firms usually call in local advisors to take account of national idiosyncrasies.

In the UPC’s first year, for example, the market is uncertain how Scandinavian judges will conduct their proceedings, also at the Nordic Baltic division. Parties also prefer national lawyers for the interpretation of national regulations in the UPC Rules of Procedure (RoP).

Ludvig Holm says, “In Swedish proceedings, we have full cross-examination and trials more similar to the UK. The UPC also has the potential for cross-examination in the RoP. Sweden is one of the few systems in the UPC with such a tradition, now that the UK has left.”

However, both Finnish and Swedish lawyers emphasise that they not only receive work from the UK, Germany and Italy, but also do business in these countries. In order to manage their network business, however, no Scandinavian litigation law firm has yet entered into a close UPC alliance with a law firm in another country. So far, Scandinavian law firms have not even joined forces in cross-border litigation.

Three diversified markets

Danish, Finnish and Swedish law firms rarely penetrate other Scandinavian markets. Roschier is one of the few law firms with a renowned team not only in its home country of Finland, but also in Sweden. Potter Clarkson also has a litigation team in Denmark and Sweden. Otherwise, it tends to be patent attorney firms such as Zacco that operate more broadly across Scandinavia.

Bird & Bird partner Henri Kaikkonen says, “From the outside, Scandinavia seems quite uniform and there are indeed many similarities. But the national patent markets in Scandinavia are quite independent as shown, for example, by the fact that Sweden has a UPC regional division with the Baltic states, and Finland and Denmark have their own UPC local divisions.”

There is stronger economic cooperation between Denmark and the south of Sweden in particular. Magnus Dahlman, who works in Gulliksson’s Lund office, says, “We here in the south of Sweden have traditionally had very close relations with Denmark. From my office, I can see the church towers of Copenhagen on the other side of the Oeresund when the weather is good. Our languages are similar, we have a comparable legal tradition and good cooperation with our colleagues in Denmark.”

At the UPC, however, everyone is now a competitor. Officially, Scandinavian lawyers do not discuss this, in view of their good neighbourly relations. But if the case and the clients would allow it, they would also be willing to conduct cases at another UPC division.

Between hope and scepticism

Ultimately, however, the UPC has so far generated only a few cases for Scandinavian law firms. The opinions of Scandinavian lawyers are somewhere between hopeful and sceptical when it comes to the UPC.

Potter Clarkson partner Lars Karnøe says, “We have seen many opt-outs in Denmark. So far, Danish clients see the UPC more as an experiment. A lot will depend on how the first judgments from the Copenhagen local division turn out. These will determine whether the clients accept the local division or not.”

Ludwig Holm, from Swedish firm Westerberg, says, “Many Swedish clients are still reticent to go to the UPC. They often think the timelines are too fast and that it is too much of a ‘German’ system.”

And the same applies to Finnish firms. Ben Rapinoja, partner at Borenius, says, “At the moment Finnish companies seem to be somewhat cautious when it comes to using the UPC. One reason is that patent litigation in Finland is often about pharma and life science. Many of these companies have opted out of the UPC for now.”

Johanna Flythstrom

So far, no lawyers in any of the Scandinavian countries have observed a negative effect of the UPC on the number of national patent cases. This is despite many of them fearing this before the UPC was launched.

English lingua franca

“Before the UPC started, many Swedish patent experts expected that the new court would effectively decrease patent litigation in Sweden for national litigation and UPC litigation,” says Magnus Dahlman.

“We have not seen any such tendency yet and we have also seen that UPC work has ended up in the Nordic Baltic regional division.”

Dahlman emphasises the language issue as one of many reasons for this. “The Nordic Baltic regional division has English as its only language,” he says. “To some extent this was met with some hesitation in Sweden at first, but it is likely a benefit for the division. Since the language is not a topic for discussion here, clients from the UK and US can be comfortable that the litigation language will only be English and nothing else.”

Scandinavian counterweight

Emil Brengesjö, counsel at Mannheimer Swartling in Stockholm, says, “A joint UPC Nordic Baltic division for all Baltic and Nordic countries part of the system would have made sense in order to create a certain counterweight to Germany, France and the Netherlands.”

“On the other hand, the current situation with three first instances in the region does not create any disadvantages, especially not for us Swedish lawyers. The Nordic Baltic regional division has got off to a good start with new cases.”

Roschier partner Johanna Flythström recognises a certain ‘wait and see’ approach with regard to the UPC. But she remains hopeful. “The general attitude towards the new system continues to be optimistic,” Flythström says.

“Also, in law firms the collaboration in international teams is seen as very positive. The moderate case load in the UPC Nordic divisions provides a strategic opportunity for parties who prefer faster proceedings to file in these venues, while benefitting from the UPC pool of judges and the pan-European system.” (Co-author: Konstanze Richter)